TDP-43 模型概述

细胞质TDP-43(或TDP43)聚集是家族性和散发性ALS的特征。虽然存在几种TDP-43聚集的肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS;也称为运动神经元疾病[MND])转基因(tg)小鼠模型,但它们各有优缺点。在我们的资源——ALS小鼠模型药物研发中,了解ALS动物模型的更多信息。

在Biospective,我们使用TDP-43蛋白病(“TDP-43模型”)的rNLS8(或ΔNLS;delta NLS;dNLS)ALS小鼠模型的原始版本和修改版本:

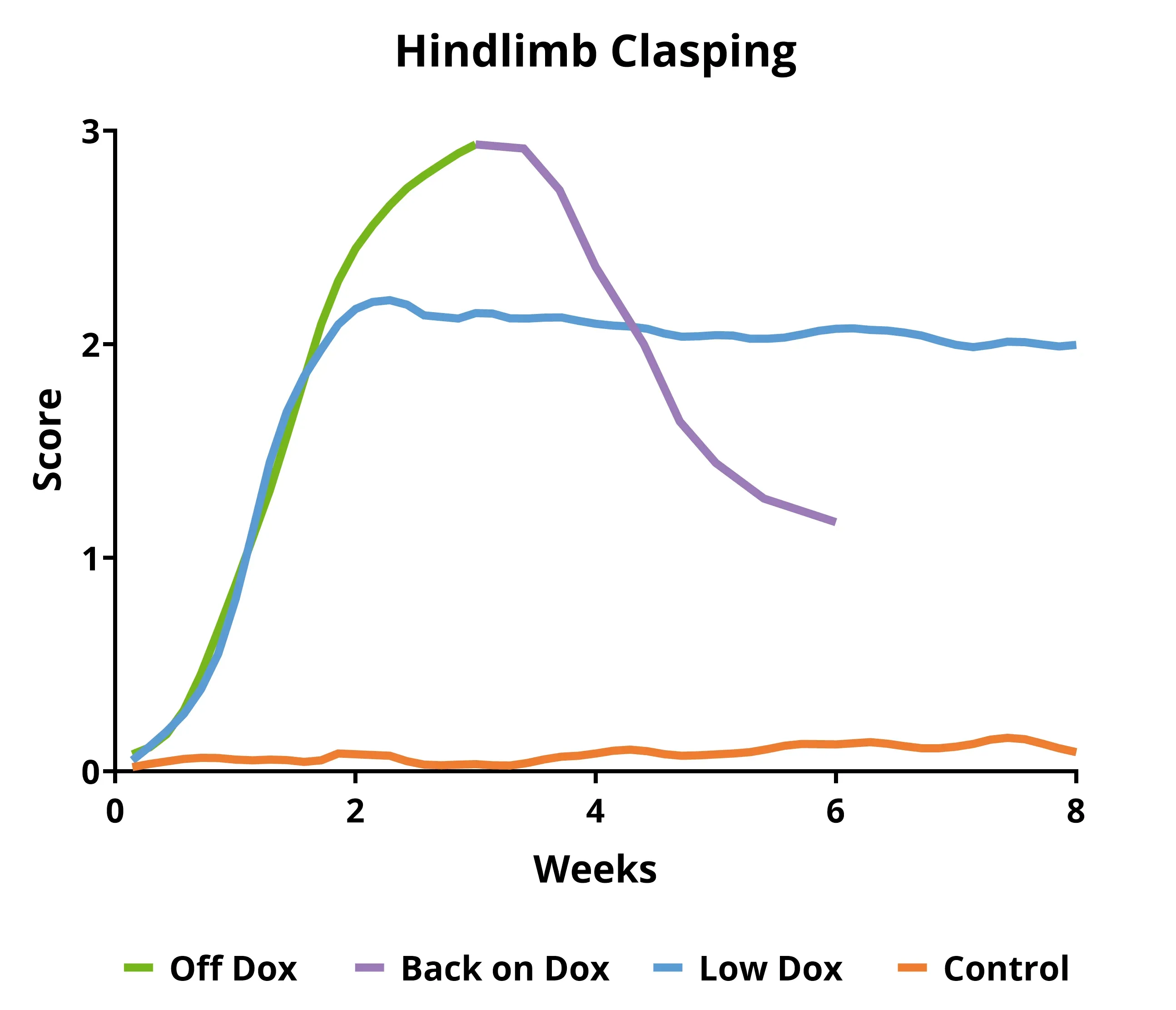

- 原始小鼠模型(“Off Dox”):进展迅速(数周

- Biospective小鼠模型(“低剂量阿霉素”):进展较慢(数月)

这些TDP-43模型对ALS研究人员的重要优势包括:

- TDP-43在细胞质中的定位错误

- 运动障碍逐渐加重

- 肌肉无力、神经退化和萎缩

- 运动神经元变性及大脑局部萎缩

- 神经炎症

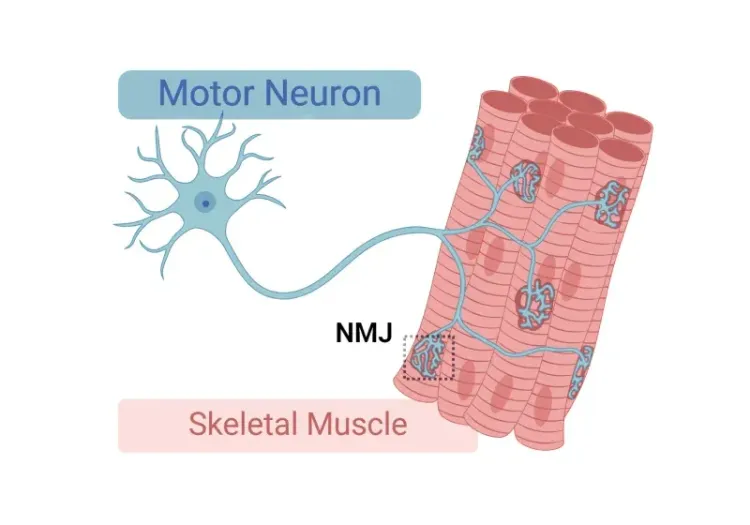

- 大脑、脊髓和神经肌肉接头(NMJ)病变

模型的时间进程是可预测的,疾病进展的测量结果具有高度可重复性,使其成为临床前研究中评估治疗药物的绝佳模型。请访问我们的资源库,了解更多信息——用于药物研发的TDP-43 ΔNLS (rNLS8)小鼠。

TDP-43小鼠

rNLS8(NEFH-hTDP-43-ΔNLS)双转基因ALS小鼠(“TDP43小鼠模型”)是通过将携带NEFH-tTA转基因的小鼠与携带tetO-hTDP-43-ΔNLS转基因的小鼠进行杂交而产生的。该TARDBP模型最初由Walker等人开发并报告(Acta.神经病理学 ,130:643-670,2015)。它是一种肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS)或运动神经元疾病(MND)模型。它也可以作为额颞痴呆(FTD)或额颞叶变性(FTLD)的TDP-43病理模型。

这些TDP-43转基因小鼠在繁殖和初始衰老期(通常为5至12周龄)以Dox饮食为主。然后,小鼠从Dox饮食转为标准饮食(“Off Dox”模型)或由Biospective开发的替代方案(“Low Dox”模型),以实现人类TDP-43的表达。该模型的一个有趣之处在于,通过让小鼠重新进食Dox,可以恢复病理和功能。

我们经过验证的TDP-43转基因小鼠测量

- 体重

- 运动评分(后肢夹紧、震颤、格栅敏捷度、瘫痪

- 握力测试

- 体内肌肉电生理学,包括复合肌肉动作电位(CMAP)(参见ALS小鼠模型和脊髓运动神经元

- 通过纵向 活体计算机断层扫描(CT)测量肌肉萎缩(参见ALS药物研发中的TDP-43 ΔNLS (rNLS8)小鼠模型

- 血浆和脑脊液中的神经丝轻链测量

- 通过核磁共振成像(MRI)测量大脑萎缩程度,以评估神经变性(参见神经变性小鼠模型中的大脑萎缩分析)

- 免疫组织化学和多重免疫荧光

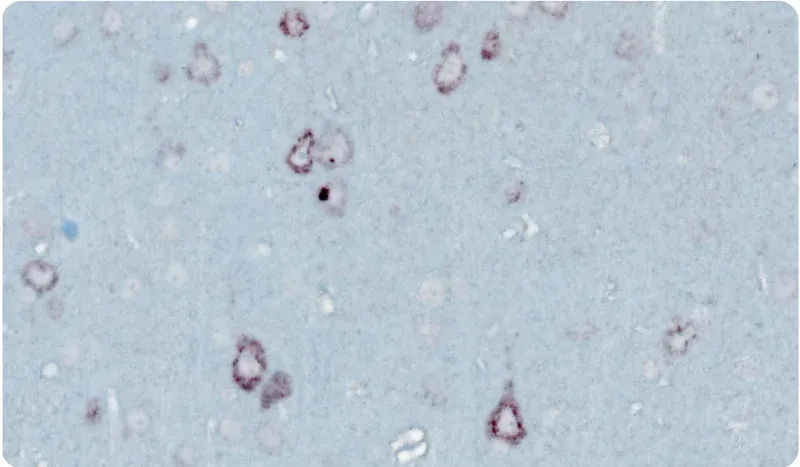

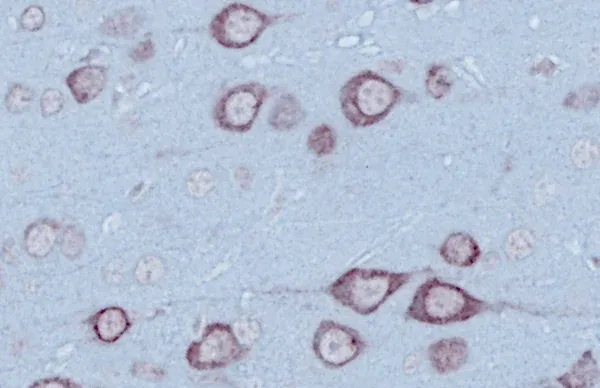

显微镜图像

显微镜图像

通过下面的交互式图像浏览器,您可以浏览我们的 TDP-43 转基因小鼠模型的整个多重免疫荧光组织切片。

您可以使用鼠标左键在图像上移动。您可以使用 鼠标/触控板(上/下)或左上角的+和-按钮放大和缩小 。您可以在右上角的控制面板中 切换(开/关)、更改颜色并调整通道的图像设置。

我们建议使用 全屏模式,以获得 最佳交互体验。

了解更多关于我们对该模型的定性、经过验证的测量以及临床前神经科学合同研究组织服务的信息。

相关内容

ALS的最新信息以及ALS动物模型治疗剂评估的最佳实践。

神经肌肉接头(NMJ)形态学与ALS模型

对神经肌肉接头(NMJ)及其在肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS)中作用的深入理解,以及用于研究NMJ形态学变化的工具和方法。

ALS 小鼠模型和脊髓运动神经元

脊髓运动神经元在小鼠肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS)模型中疾病进展的概述。

ALS小鼠模型用于药物研发

指导如何最有效地使用肌萎缩侧索硬化症(ALS)的实验动物模型(小鼠和大鼠模型)进行临床前治疗测试。

TDP-43 ΔNLS (rNLS8) 小鼠用于ALS药物研发

该资源提供了有关使用ΔNLS(deltaNLS、hTDP-43ΔNLS、hTDP-43DeltaNLS、dNLS、TDP43 NLS、rNLS8)TDP-43 ALS转基因小鼠模型进行临床前治疗研究的信息。

ALS、阿尔茨海默氏症和帕金森氏症中的微胶质形态

概述微胶质形态学分析及其在神经退行性疾病研究和药物研发中的应用。

自噬与神经退行性疾病

细胞自噬在脑健康和神经退行性疾病中发挥作用的概述。

自噬和转录因子EB(TFEB)

转录因子EB(TFEB)及其在自噬和神经退行性疾病中的作用概述。